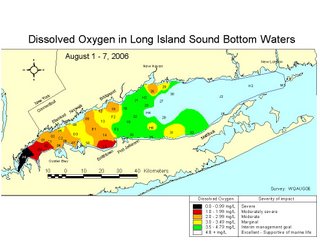

Before I get on with today’s hypoxia post, I thought it wise to remind myself and anyone else who reads this why hypoxia is important. Nitrogen inputs and low dissolved oxygen concentrations mean nothing unless you remember this: Long Island Sound is an estuary that is supposed to be crammed with sea life of all kinds, but when hypoxia hits, when dissolved oxygen concentrations drop, marine life – fish, lobsters, crabs, whatever – can’t live in the Sound. They either die or are forced elsewhere, leaving a void. And, as Penny Howell, a fisheries biologist with the Connecticut DEP once told me, stating the obvious with simple eloquence: “Marine systems aren’t supposed to be voids. There’s supposed to be something there.”

Which leads me to Sam Wells, the transplanted Nutmegger who comments here so frequently from Texas that my wife thinks he’s on my payroll. Sam asked an interesting question

in the comments to yesterday’s post about hypoxia. He wrote:

I've been thinking about this for a long time ... but can anyone tell me when the summertime waters closer to New York were anything but hypoxic?The answer for Long Island Sound is yes, and it can be found on page 119 of

this book. I’m immune to copyright violations on this, so I’ll summarize and quote: 15 or so years ago, Paul Stacey of the Connecticut DEP asked the same question. He figured that one way to come up with an answer was to determine how much nitrogen flowed into the Sound 400 years ago, before there were any sewage treatment plants or developed areas that contributed nitrogen.

“The key to that calculation was finding waterways that could be presumed to be carrying the same amount of nitrogen as they had four centuries ago …. He found two streams that met those qualifications: Burlington Brook, which flows through the town of Burlington, into the Farmington River and then into the Connecticut River and the Sound; and the Salmon River, a tributary of the Connecticut that cuts through East Hampton and Glastonbury.”The USGS had been testing and keeping records of the amount of nitrogen per liter of water in those streams. Stacey was able to apply that amount to the flow rate of all the Sound’s tributaries.

“He discovered that, four centuries ago, about forty thousand tons a year of nitrogen had flowed into the Sound from its tributaries. Stacey had that number plugged into a computer model of the Sound and came up with another estimate: in a typical year before the Sound’s watershed was settled by European colonists, dissolved oxygen in the western end of the Sound never fell below about 5.5 milligrams per liter, which was plenty to keep even the relatively shallow waters … habitable for marine creatures.”Today, in addition to that baseline of 40,000 tons,

sewage treatment plants release an additional 29,000 tons a year (which is down from 38,700 about a decade ago) and an uncalculated amount reaches the Sound through stormwater runoff, which accounts for the awful conditions that beset the Sound each summer.

Johan Varekamp, the Wesleyan professor of Earth Sciences who spoke at April’s Long Island Sound Citizen Summit, seemed to be confirming Stacey’s analysis when

he said at the conference that his research shows a striking increase in the amount of nitrogen that reached the Sound as long ago as the early 1840s, which he attributed to increased development and land use changes.

So to answer Sam’s question: there was no hypoxia 400 years ago, and hypoxia probably wasn’t all that bad 170 years ago. But it’s bad now, and not just in the Sound.