I took my time getting to the Long Island Sound Citizens Summit conference in Bridgeport on Saturday, because I’ve been to a lot of conferences and good ones are very rare. I was hopeful about Saturday’s, but in truth I went as much out of obligation as anything else.

But I was wrong. It was a terrific conference in more than one sense, and Save the Sound/Connecticut Fund for the Environment deserves credit for getting a lot of good speakers, for attracting a big crowd, and for persuading a lot of news media people to cover it.

The first thing I was wrong about was the size of the crowd. I had figured fewer than 100 people would attend. But the big meeting room at the Holiday Inn in Bridgeport was filled by the time I got there, at 9:45 (about 45 minutes late), with about 160 people. Somebody made a comment later about how the conference was preaching to the choir. This was certainly true, but I consider it to be a good thing. This is an important time for the Sound politically and ecologically, and preaching to the choir is an excellent way of strengthening and solidifying the Sound’s base of supporters. So preach on.

I made a list of people I knew who were there (and it goes without saying that there were a lot of people I didn’t know): Mickey Weiss of Project Oceanology, Paul Stacey and Mark Parker of Connecticut DEP, Sandy Breslin and Tom Baptist of Audubon Connecticut, Bob Funicello of Westchester County, Peter Sattler of the Interstate Environmental Commission, Bill Boysen of SoundWaters, Dave Burg of Wild Metro, Vince Breslin (and a bunch of his grad students) from Southern Connecticut State, Nancy Seligson and Shelia O’Neill (former board members of Save the Sound), Martha McCormick Smith of Yale, Karen Chytalo of New York State DEC, Emmett Pepper and Maureen Dolan of Citizens Campaign for the Environment, Kiki Kennedy (board member of CFE), among others. And between Vince Breslin’s students and others who I think were from Columbia University, there was enough new blood to be encouraging.

The first speaker was Gina McCarthy, the Connnecticut DEP commissioner, and I confess that I tried to time my arrival to miss most of her talk – I’ve heard commissioners give speeches before, and generally they consist of one long platitude. I probably heard about half McCarthy’s talk, and I was impressed with her irreverence, her lack of pomposity, and her wit.

And with her New England accent. The theme of the conference was climate change, and she talked, for example, about how changes in the amount we drive and the kinds of vehicles we drive can make a big difference in the amount of greenhouse gases we’re responsible for. “The koz you drive are important,” she said, “and there are great koz out there that you can purchase.”

Once I figured out what koz were, I agreed wholeheartedly.

As I mentioned, the event got good press coverage (

here and

here), and so I’m not going to summarize the proceedings. But I picked up some interesting facts and observations.

Joop Varekamp, who grew up in Holland in the 1950s and ‘60s and who now teaches science at Wesleyan University, said that when he was a boy he could skate from town to town on the frozen canals in winter. It’s been years, though, since the canals have had sufficient ice.

Varekamp studies the sediments from the Sound area and draws inferences, about pollutants and about global warming. He said, for example, that sea level rise, as measured near the mouth of the Housatonic and the mouth of the Connecticut, was one millimeter a year in 1660, 1.7 a year in 1900, and 3 a year in 2000 – clear evidence of global warming.

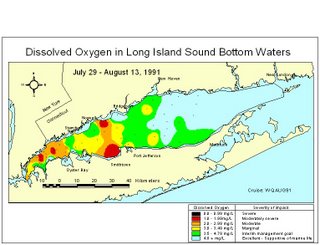

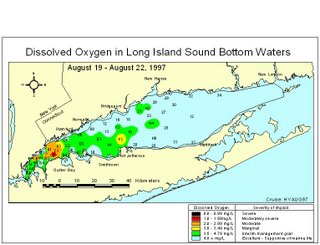

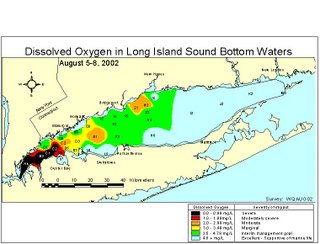

In the Middle Ages there was a significant warming period, he said, but it was not enough to cause hypoxia. From that he infers that global warming alone hasn’t been enough to cause hypoxia.

Hypoxia, he said, is clearly a result of the increase in sewage and nitrogen dumped into the Sound – an increase that was measurable as long ago as the early 1800s. Therefore, he said, the data support the Sound cleanup program. It’s expensive, but “ultimately it is going to pay off and it is going to bring back the waters of Long Island Sound.”

At which point I’m pretty sure I heard the many people in the room who are working on the Sound cleanup exhale in relief.

Robert Whitlatch, of the University of Connecticut, talked about invasive species, and said biodiversity is clearly important to a healthy ecosystem: the more diverse an ecological community is, the less vulnerable it is to invaders.

Unfortunately a previously unknown sea squirt, called

Didemnum, has moved in from the east and is now covering the sea floor in the eastern end of the Sound. Its skin has a pH of 2, so nothing grows on it. It has changed foraging areas for fish and recruitment areas for blue mussels, and not for the better.

David Conover of Stony Brook University explained that for fish, Long Island is a transition zone – it is the southern end of the range for some northern species and the northern end of the range for some southern species, which makes the Sound different from Delaware Bay, for example, or Massachusetts Bay.

Twenty years of trawling by the Connecticut DEP has shown that the numbers of southern fish such as weakfish, summer flounder, black sea bass and hickory shad are all higher. Northern species such as winter flounder, Atlantic herring, and lobster are all down. (I asked why we should care that we're losing northern species if southern species are moving in to replace them, and he conceded that it's a value judgment: people like to catch winter flounder and lobsters, for example, and both are less abundant. But they also like to catch summer flouder and black sea bass, so to me it doesn't make much difference.)

During the Q&A session, lots of people wanted predictions of the future. Conover said one of the problems is that so many ecological changes are happening simultaneously that it is impossible to predict and very difficult to manage risk.

“What we are doing with planet earth,” he said, “is a massive experiment from hell.”

On that cheerful note, I’ll go back to an issue of critical importance to anyone sitting in a meeting room for five hours on a Saturday. I’m talking, of course, about PowerPoint. Suffice it to say that I hate PowerPoint presentations, that they are badly misused by speakers, and that rather than improve communications PowerPoint has become a barrier.

Speaker after speaker on Saturday spent their entire time at the podium looking at their PowerPoint slides on the screen rather than talking to the audience. I felt like yelling, “We’re out here! Talk to

us!” (Varekamp and McCarthy were exceptions in that they actually looked at us while talking to us, and Lynn Stoddard of the Connecticut DEP didn’t use slides at all, which should put her at the top of the invitees list for future conferences.)

Speaker after speaker gave us brief glimpses of complicated graphs designed for a college science classes and expected us to grasp what they were illustrating. And one speaker apologized because the information on his slide was too small to read. This led me to conclude that, generally speaking, if you feel it necessary to say you‘re sorry because your slide is unreadable, it’s probably safe to get rid of that slide.

But I quibble. As I said, it was a terrific conference, well worth a Saturday. And by the way, I ran into

some of these nice folks (I think they are members of a civic organization), who were staying at the Bridgeport Holiday Inn while attending a funeral. They were in my way as I tried to walk through the front door but I didn’t feel the need to quibble with them.

And now some related digressions…

Digression 1: When you spend the day in Bridgeport, you feel both sad and a bit awestruck. Awestruck because as you drive or walk around, it’s obvious what a terrific place downtown Bridgeport used to be; sad because when the great manufacturing industries left, the city lost its economic vitality (and putting I-95 through Bridgeport was a horrendous, community-killing move as well).

People who actually know what they’re doing and what they’re talking about haven’t been able to help Bridgeport much, so I’ll keep my mouth shut about it. But the New London Day has

an interesting story about another old waterfront city, Norwich, and how there are hopes to use at least one of the old mills.

Digression 2: And for another example of how highways can destroy communities, read

this, from the New Haven Register, about Route 34. Truth is, the city probably ought to think about tearing the whole thing down.

Digression 3: If we needed an illustration of the conflicts that will arise as sea level rises, the

Stamford Advocate has a story about a good one. A homeowner on Stamford’s Shippan Point – not the shabbiest of neighborhoods – wants to build a seawall to stop his bluffs from eroding. The DEP is saying not so fast: bluffs are an important coastal resource and you need to find a different way of protecting them.

Digression 4 (unrelated to anything I heard or saw at the conference): there’s a classic use conflict going on on the lower Mianus River between lobstermen and a businessman who doesn’t like having the lobstermen around,

here.

Digression 5: Curt Johnson, an attorney for CFE, mentioned to me during the lunch break that a committee of the legislature was putting $50 million into the Clean Water Fund. I refrained from bragging that I had

had that scoop on Friday, courtesy of Terry Backer. Curt said that a lot of the credit should go to

the Coalition for Funding the Environment, which lobbied hard, and to CFE itself, which generated more than 100 phone calls and e-mails to Hartford. I agree. Good work.